Fiona Mavhinga, Executive Advisor for the CAMFED Association

Why ‘big sisters’ matter

I'm Debora, a Learner Guide and school Matron in Tanzania. Once a vulnerable girl myself, I mentor students in Tanzania, helping them stay safe, stay…

Fiona Mavhinga, Executive Advisor for the CAMFED Association

Millions are desperate for a better life — for an education — without the means to go to school, and thus in grave danger of being exploited. They are the first to be failed by the system — at risk of early marriage and teen pregnancy, which can have huge ramifications for their physical and mental well-being.

People talk about child marriage causing these girls to abandon their education. But it’s often a failing education system that’s the real root of the problem: Under resourced schools, a lack of well qualified teachers in rural areas, long and dangerous distances to school, and the costs that go beyond school, exam and uniform fees. Sometimes even the price of a notebook or a pen is insurmountable for families living a hand to mouth existence. Yet girls’ zeal for education is so strong, and this leads to exploitation. Imagine the irony of finding that transactional sex is your only means of securing funding for your education, then ending up pregnant, HIV positive, or a child bride who is pushed out of school. All of these outcomes perpetuate the cycle of poverty. A quality, responsive education system is the key to breaking this cycle. That’s what we need to focus on delivering.

Me speaking at the Girls’ Education Forum, highlighting that those who have lived poverty and isolation have a nuanced understanding of the barriers to girls’ education, including girls’ psycho-social needs. Photo: Russell Watkins/DFID

The Girls’ Education Forum hosted by the UK’s Department for International Development (DFID) earlier this year was a good example of the sort of galvanizing activity we need. Among a number of commitments from academic institutions, NGOs and governments, DFID pledged a further £100 million to advancing education opportunities for girls who have dropped out or never been able to access.

These are strides in the right direction. But there are two big things we must get right if we are to find telling solutions for girls’ education.

The first is that we need to ensure that investment supports a girl holistically, and that communities are deeply involved in making these investment decisions.

Investment needs to help tackle all of the challenges she faces as a young person trying to get an education. For example, funding a new school library is great — but we also need to think about whether she has shoes to walk to school every day. Whether she has the support of her family, her community and her government to make her believe she is entitled to an education. We have to look at the whole picture.

The second is that we must draw on the shared experience of those who have lived and tackled the extreme vulnerability of marginalized girls, to ensure we’re really addressing her needs holistically. They are the experts. They know what it takes to change the context for girls for good.

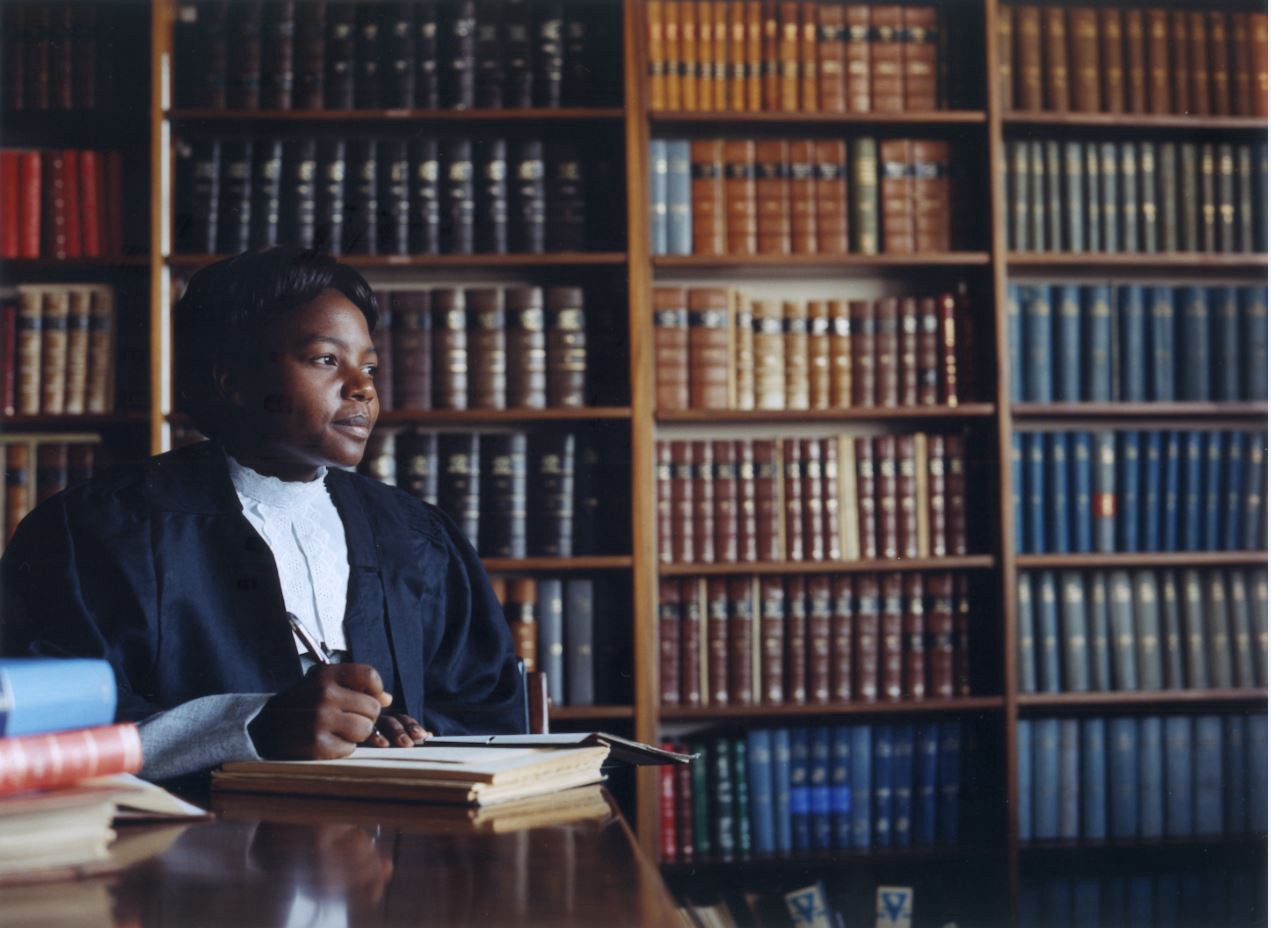

When I qualified as a lawyer in Zimbabwe, I worked in a practice with one other woman among 13 men. Photo: Mark Read/Camfed

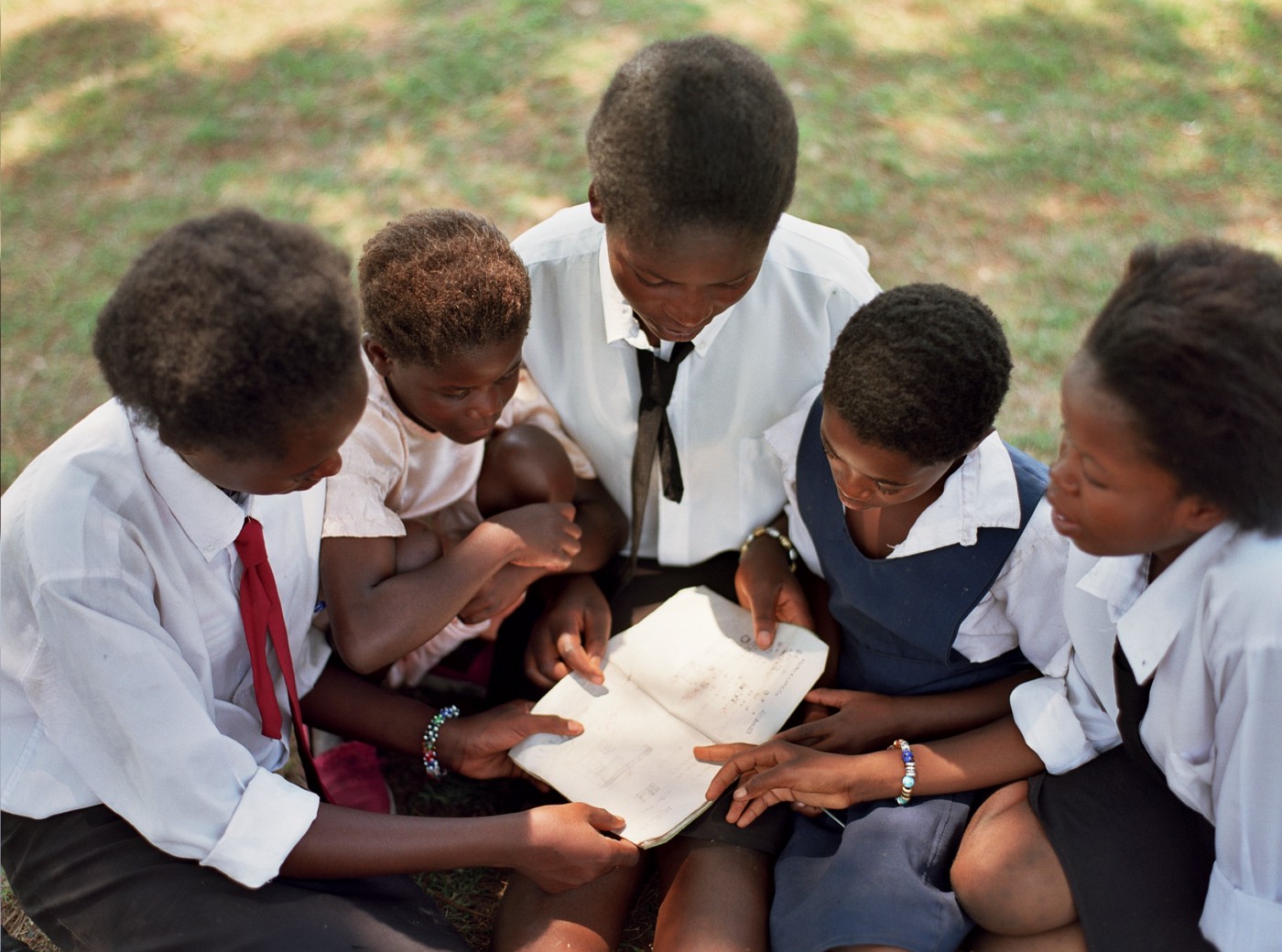

I know the importance of this more than anyone. My life today stands in sharp contrast to my life as a girl in rural Zimbabwe, getting up at 4 am, selling vegetables on the market with my grandmother, trying to make enough money to pay for food and my school going costs. I was fortunate to escape. With the support of my family, my community, and Camfed — an organisation committed to providing holistic, community-based support — I did well at school, went on to university, and became a lawyer. My story — of a girl struggling to maintain her grip on education — is the story of millions of girls around the world. So many of my friends in my rural village lost that grip, and my life is so drastically different from theirs today because of one thing: a quality education.

Together with the first 400 young women who graduated with Camfed’s support, I helped to create the Camfed alumnae network — or CAMA. We are now helping other girls get the same chance that we had. This network of women supports the next generation of disadvantaged girls in rural Africa get the education they are entitled to, providing mentorship, developing and leading education programs, and working with communities and schools to create quality learning environments. Most importantly, they listen to the needs and challenges faced by these girls.

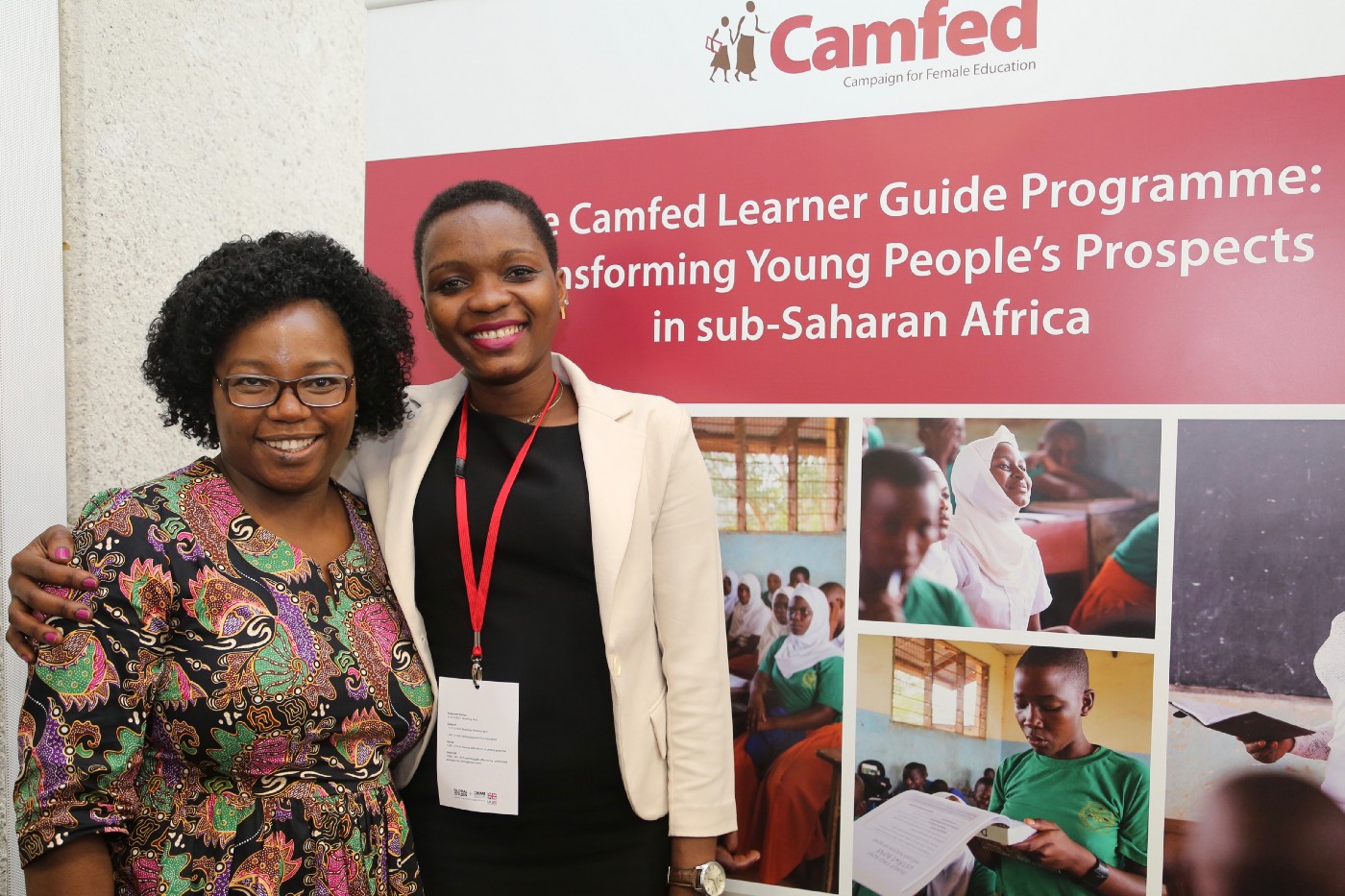

Me with some of my CAMA sisters, working to change prospects for girls in impoverished rural communities

Today there are 55,358 of us across Zimbabwe, Zambia, Ghana, Tanzania and Malawi. We have the expertise. All we need is the technology and the resources to support this powerful movement.

If we are to transform broken education systems in some of the poorest regions around the world, it’s vital we start to find solutions that work. Solutions like the Camfed Learner Guide Program, which includes alumnae in the development and delivery of a life and study skills curriculum, and provides the crucial mentoring and female role models so important to girls vulnerable to exploitation. Right now we are working to extend this model and provide transition support for young women school leavers, bridging another period of great vulnerability.

I want to call for everyone — whether they are policy makers, non-profit leaders or everyday citizens looking to make a difference in the world — to listen to the real experts in girls’ education. To listen to those, like our CAMA members, who know what it is to escape poverty through education.

Learning from these women is crucial if we are to deliver the change we need, and deliver it now. All of our futures are at stake.

This blog was first published in the Huffington Post on International Day of the Girl.

Fiona Mavhinga was one of the first girls supported by Camfed (the Campaign for Female Education) in Zimbabwe. She is a lawyer, and a founding member of Camfed’s CAMA alumnae network. Today she leads on the development of the CAMA network, which is projected to grow to 130,000 by 2019, as a direct result of Camfed’s investment in girls’ education.

My colleague Nasikiwa and I introducing the Camfed Learner Guide Programme at the UK’s Girls’ Education Forum. The curriculum was developed with CAMA members, who are now returning to their local schools to deliver a contextualised life and study skills programme, and act as vital mentors and role models to vulnerable girls. Learner Guides connect families with schools and services, and return child brides to school. Photo: Sarah Winfield/Camfed

I'm Debora, a Learner Guide and school Matron in Tanzania. Once a vulnerable girl myself, I mentor students in Tanzania, helping them stay safe, stay…

I decided to join the Mother Support Group because I wanted to counsel girls and help them progress in education. It feels really good that…

Deborh Case $500

Aimee Miller $158

Lucinda Morrisey $158

Emily Reardon $1052

susan. J Feingold $26.6

Jacqueline Davis $158

Susan Strome $4000

Angela Thompson £80

Paul George $158

Benjamin Woodbridge $400

Jacquelyn Sullivan $1262

Lenore Denise Williams $3000

Jill Pask £124.9

Karen Mura $150

Tracy Melin $263